My imposter syndrome kept flaring up. Our escalator was carrying us closer and closer to the blue door that separates Per Se from the rest of Manhattan and I still felt uncertain about my motivations for the visit. Was I really eager to broaden my culinary education or just hoping for a glimpse of the 1%?

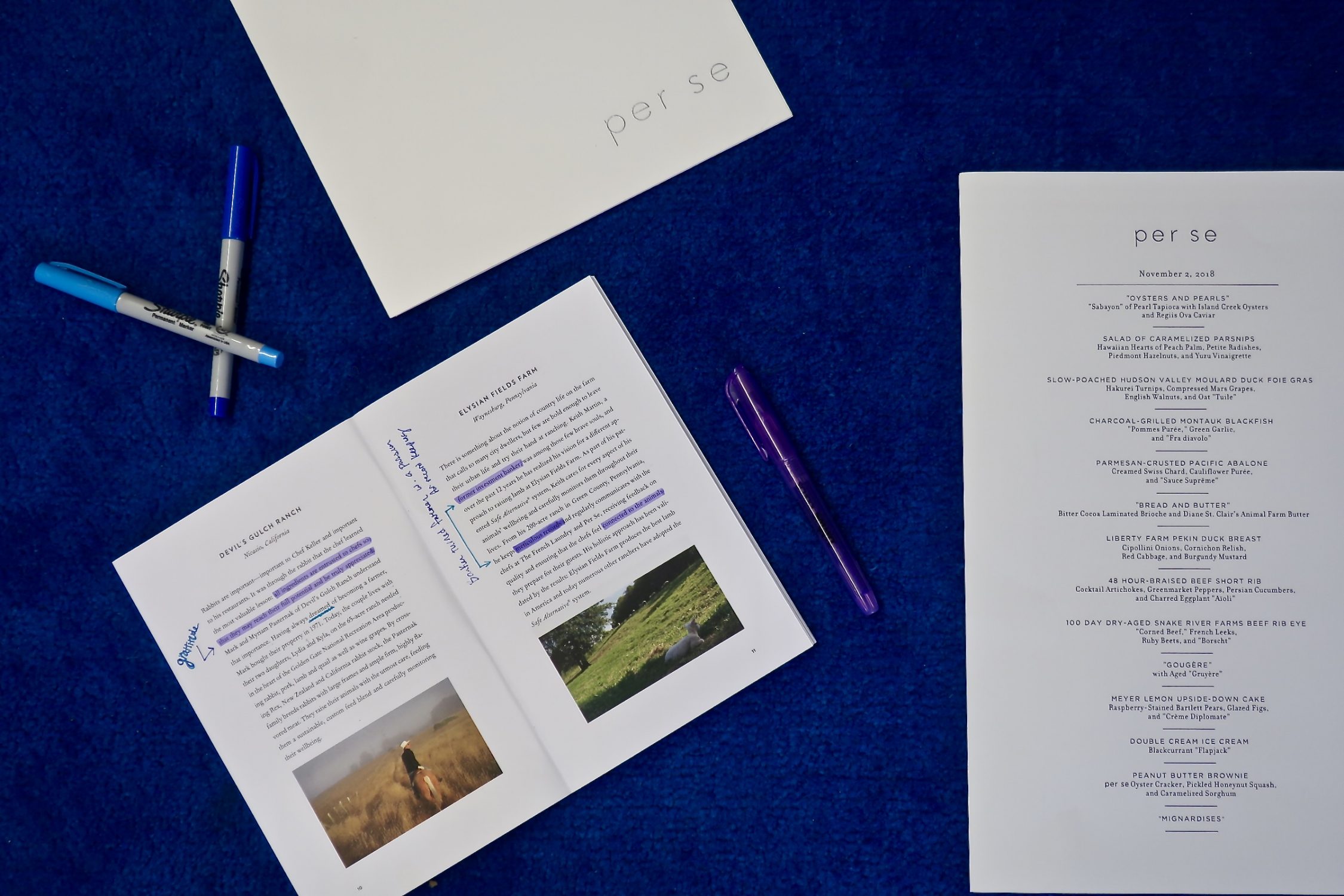

I knew that writing about the experience would mean admitting to my ardently frugal family that I had spent a small fortune on a single dinner. Three-Michelin-stars, nine-courses, and a month’s rent.

Deadhorse hill chef-owner Jared Forman reminded me later that it hadn’t been such an expensive meal when you considered how many people had touched the food before it arrived at our table.

I’d like to say I knew this first hand; after all, I had ventured back to the kitchen at the end of my visit. But, Forman told me I was mistaken.

According to him, I met only a fraction of the cooks tasked with crafting my meal. What I had witnessed was the main kitchen, complete with a live feed tuned to Thomas Keller’s first love — The French Laundry in California. The commis kitchen had been kept out of site.

Forman has spent enough time picking herbs, topping eggshells, and opening oysters at Per Se to know the difference.

Johnson & Wales students compete every trimester for a prestigious Per Se internship. More than a decade ago, Forman earned the coveted spot, landing him a four month stint in Keller’s kitchen. The commis kitchen, that is, where the prep cooks toil away until (if they’re lucky) they are called up to run the cheese station before progressing to the role of fish roaster, and so on and so forth. No matter how much time they spend at Per Se, there will only ever be one man at the top.

Keller is one of the most celebrated chefs in history. He currently holds seven Michelin stars, three at Per Se, three at The French Laundry, and one at Bouchon. The Michelin guide is something of a restaurant bible. One star represents “a very good restaurant,” two stars signify “excellent cooking that is worth a detour,” and three stars mean “exceptional cuisine that is worth a special journey.”

Forman started at Per Se just after Keller had finished consulting on Ratatouille, an Academy Award winning animated film about a rat who becomes a chef. Forman’s arrival at Per Se came only a week after the photos for Keller’s second book, Under Pressure, had been shot at the restaurant.

Keller’s books are not meant to cook out of.

“Half the recipes don’t work. It’s not about recipes. They’re about inspiration,” Forman says, “When his first book came out, there was nothing else like it.”

“Half the recipes don’t work. It’s not about recipes. They’re about inspiration,” Forman says, “When his first book came out, there was nothing else like it.”

When his internship ended, Forman parlayed his newfound experience into a job at David Chang’s momofuku noodle bar. “Per Se is like a coloring book. You color in these lines and then go home. You have a very real barometer of what success and failure is because Thomas Keller’s there to tell you what it is,” Forman says.

He recalls one cook on the line who wore a bracelet embossed with WWKD, as in, “What would Thomas Keller do?”

He says he knows better than to compare Per Se to anywhere else he has ever or will ever work, but in four short months, he admits that the restaurant showed him something remarkable.

“Per Se is not a cutthroat kitchen. At some high end restaurants, people steal mise en place. People sabotage each other,” Forman remembers, “At Per Se, there’s a greater vision embraced by everybody. People are firm and strict, but it’s always with purpose.”

Initially, Forman scoffed at the notion of my visit to Per Se.

“I don’t think it’s the best food in the world. It’s not the most groundbreaking food, anyways,” he said, “It’s a place you go for precision and perfection and we should all be glad it’s there for that. You go there for technique.”

I explained to him that I was deep in pursuit of the standards that shaped deadhorse hill in Worcester in addition to America’s vision for fine dining.

He rolled his eyes and said, “I just hope someone else is paying.”

Behind the Blue Door

The restaurant consists of 66 seats perched high above Columbus Circle, along with a private dining room that accommodates no more than 30 guests behind boardroom glass and brown curtains.

Per Se fosters steadfast dedication in its staff.

Servers fetch clean bills from the bank every evening to ensure that you don’t end up with the wrinkled change from someone else’s pocket. Reservations are on point. The floral arrangements are fit for the Royal Wedding. The napkins might as well be cashmere blankets. And the charger plates offer some sort of Magic Eye pattern from which I kept hoping a sailboat or a spaceship would reveal itself.

The moment I attempted to set down my purse on the back of my chair, a tiny stool appeared at my side, as if by magic.

“Why not begin with champagne?” we asked. The salmon cornet with tartare and crème fraîche, balanced on an ice cream cone, practically demanded it, as did the oysters and pearls — a custard of tapioca and Regiis Ova caviar.

Like everything else, these petite bites were quite intentional. “His philosophy is the idea of diminishing returns; as you’re eating something, you get used to it. Keller never lets this happen,” Forman explained, “Your palate never gets accustomed.”

The courses unfolded in such a way that each one proved more personal than the last.

Take for example, the slow-poached Hudson Valley moulard duck foie gras for which the ducks are hatched and harvested humanely by a former member of the Israeli Armed Forces and his partner who notably worked on Wall Street before he got into the liver business.

Even the bread course arrived with an announcement that the butter hailed from a cow named Keller, milked twice a day by a dedicated dairy farmer in Orwell, Vermont.

I do not work for a fancy firm with a standing table, I have never been to a restaurant quite this formal, and I suspect I butchered the pronunciation of the 2015 Patrick Piuze I was drinking.

I visited Per Se for the anecdotes. The tales our servers told us made the smell of charcoal-grilled blackfish more intoxicating and conjured visions of the Pacific coast before the parmesan-crusted sea snails had so much as touched my lips.

It’s probably for the best that I didn’t receive my booklet of purveyors until after the meal. Not because I would have felt dismayed to devour the Liberty Farm duck breast while observing the fourth generation farmer cuddling with one of his flock. On the contrary, I fear I’d have been so engaged in his one page bio that I’d let the poor pekin grow cold on my plate.

The same is true of the 100 day dry-aged Snake River Farms beef rib eye. Aside from its concentrated flavor and the well marbled meat, I’d have hastened to detect its diet of barley, golden wheat straw, alfalfa hay, and Idaho potatoes had I known it existed.

The dessert courses arrived all at once in a flood of raspberry-stained Bartlett pears, pickled honeynut squash, and blackcurrant flapjack ice cream. The “mignardises,” French for bite-sized dessert, may as well have been blown from delicate bits of colored glass.

Along with my booklet of purveyors, I was sent home clutching a branded bag filled with carefully wrapped mignardises and tins of shortbread — parting gifts. I also received an invitation back to the pristine kitchen.

When I told Forman about the back of house tour, he recalled this was not out of the ordinary.

“Some people don’t want to see behind the scenes. Other people get a crazy kick out of it,” he said, “They probably googled you when you made the reservation and knew you’d be into it.”

The Myth of Perfection

The literature inside my Per Se gift bag includes a note from Keller himself. “When ingredients arrive at the restaurant they are, in one sense already finished,” he wrote, “At the stove, we have no control over how an animal was raised or the way a peach was harvested. As chefs, all we can do is to carefully select our suppliers and then work with them to ensure we get the best possible ingredients.”

I have heard Forman express similar sentiments. He feels lucky to live in a place with so many amazing farms and wild habitats capable of turning out the sweetest corn and the most pungent ramps.

“The distribution system to Worcester has exploded over the past few years, which allows us to combine all of these local products with other amazing things from across the country and around the globe,“ Forman told me, “A huge chunk of my time in any given week is spent sourcing products for the restaurant, visiting farmers markets and ethnic markets, weeding out specialty items, and talking directly with farmers. The details are absolutely endless.”

Two weeks after my visit to Keller’s kitchen, Forman loaned me his copy of The French Laundry Cookbook.

Sitting at home in my Worcester apartment, I cracked the heavy volume open in my lap and a line leapt right off the page. “When you acknowledge, as you must, that there is no such thing as perfect food, only the idea of it, then the real purpose of striving toward perfection becomes clear: to make people happy, that is what cooking is all about,” Keller had written.

Per Se showed me precision, technique, and urgency, but the experience didn’t earn me any degrees or badges. I had not been an imposter at Per Se anymore than I am an imposter in my own kitchen. Keller had relished the chance to make me happy, and he had immeasurably succeeded.

In the weeks that followed, I would struggle to rattle off finite details of the nine course menu I so enjoyed at Per Se, but the memory of a blissful evening never left me.

Maybe you have the cash to let chefs like Forman or Keller help you find happiness in your food on a regular basis, but most people don’t. The perfect dish is the one that brings contentment and it could cost you next to nothing if you’re willing to treasure it properly.