Despite all of the news about economic globalization with big box stores and a deep decline in numbers and importance, public markets are undergoing a resurgence as people demand to rebuild local economies and increase human interaction. Taking the back seat in the discussion of food distribution and the obligation of trust between vendors and shoppers since the mid-20th century, public markets are finally reclaiming their stance on the importance of increased access to fresh foods, diversity and the embodiment of community engagement.

In Public Market and Civic Culture, historian Helen Tangires writes, “The public market is a key piece in understanding the profoundly important shift from agrarian to industrial food systems in 19th-century America.” Considered as a place thriving for elements beyond the sale of food, public markets were civic spaces and a common ground “where citizens and governments defined the shared values of the community.”

The earliest American markets brought together farmers, fishermen, and other food producers with the townsfolk and merchants at scheduled, open-air events. With Boston’s rapid growth in the early days of the colony, John Winthrop wrote of a public marketplace on Great Street and it remained as the first record of a public market in the New World. With popularity came density and quickly, the outdoor, open-air events needed reconsideration and relocation. In 1742, Peter Faneuil built Boston’s first market hall which expanded until 1826 with the opening of Quincy Market. By this time, public markets were social and political hubs for cities like New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore.

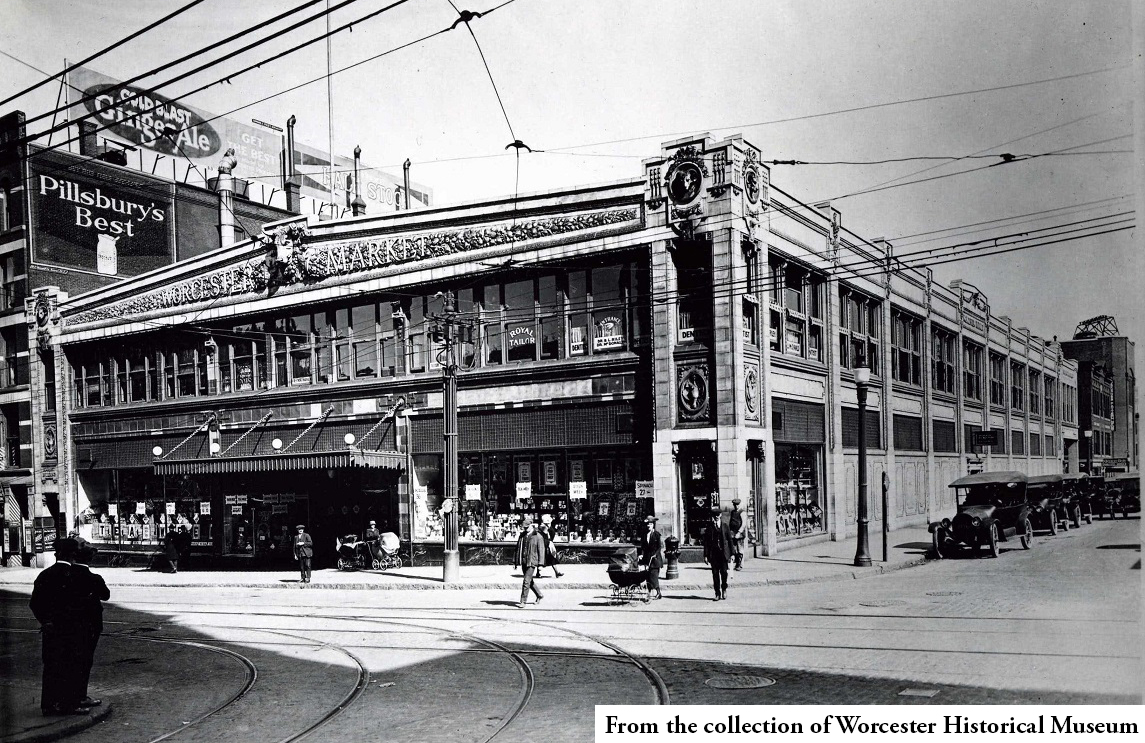

Even in Central Massachusetts, the Worcester Market Building opened in 1915 with a terracotta facade that brought iconic agricultural imagery to the corner of Main and Chandler Street. By 1917, 25,000 customers visited the market on a typical Saturday and the building had capacity to accommodate 4,500 shoppers at a time. And, aside from being the largest market in the country for more than a decade, The Worcester Market Building was also the most sanitary. With a startlingly deep foundation of reinforced concrete and non-absorbent floors, the building was deemed “absolutely rat-and-vermin-proof” by its original operators.

Their place in culture was short-lived with the advent of supermarkets’ emphasis on convenience and lower prices—as a result from larger purchasing volumes. The supermarkets, intended to challenge the dominance of food retailers, became a major impact on public markets in Boston and throughout the country as it affected food consumption and buying habits. The close-knit social fabric once admired by patrons of the public markets like Faneuil Hall and Worcester Market was quickly traded for convenience and less-engaging human interaction while shopping. The supermarkets adopted elements of the public market style with the appearance of fresh produce, the inclusion of fish and meat markets, all while moving further away from the element of civic space and common ground.

Now, between the emergence of supermarkets and the slow demise of public markets, there was an unseen growth for farmers markets. According to data from the USDA, the number of farmers markets in the United States has grown by 76% since 2008, registering over eight-thousand markets on the USDA’s National Farmers Market Directory. In a recent survey analyzing the reasons for shopping in farmers markets, 63% of responders answered that freshness was their prime reason, 54% indicated price savings and 12 percent attributed their shopping habits at farmers markets to the social atmosphere. Farmers markets, in essence, provide the same quality and ethical shopping experience consumers valued from public markets, but without the stability of year-round shopping options and permanent locations.

Since the vital burst of farmers markets, Boston responded with the opening of the Boston Public Market, after decades of a marketless downtown. An indoor, year-round marketplace featuring 35 New England artisans and food producers delivering fresh produce, meat and poultry, seafood and prepared meal options, the Boston Public Market has become an instant success. A local shopper described the new location as “a dream come true” because of its diverse food options and accessibility to fresh, low-cost produce. Vendors and businesses like Noodle Lab – a ramen noodle shop – and Union Square Donuts find comfort in the Boston Public Market for its ability to bring in a diverse food traffic outside of their normal demographics. “We want to share our donuts with as many consumers as possible and having a shop located in the Boston Public Market is an ideal addition to our lineup of locations,” said a Union Square Donuts employee. Although the already prepared foods are the biggest elements to the public market experience, the Boston Public Market also houses producers and farmers from Appleton Farms, the Massachusetts Cheese Guild, and Chestnut Farms to give consumers access to freshly farmed vegetables, organic products and unique cheeses and wines. The Boston Public Market Association developed and operates the Market with public impact goals to support: economic development, New England food system resilience, public health and education, affordability and access and Worcester is on the brink to do the same.

In the midst of a growth spurt, Worcester looks back on its roots in an attempt to infuse what the city needs the most: a common space to define and explore shared values among the diverse culture that breathes life into Worcester’s identity. In the Canal District, the Kelley Square market, Harding Green, seeks to provide a “focus on community, the local diversity and embrace human interactions with ethnic street foods,” according to businessman and owner, Allen Fletcher in a recent interview with Mass Foodies. While this new public market may be the tipping point Worcester needs to readdress the consumer buying habit, it can also add to the city’s current influx of farmers markets and inadequate access to fresh foods.